Airport Food

I get depressed at airports.

Adam Carolla

Despite the best efforts of the elite big city airports, airport food blows.

Even the wonderful restaurants recruited to open inside fancy airports lose their magic to the vague sense of unease that comes with being trapped inside a secured building.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Some airports are built different - like Big Creek Airport in the northern Rocky Mountains.

Getting there can be tricky - there’s no bus, train, or car service - access is limited to horseback, walking, or flying. And if flying, remember the runway could use some maintenance.

The flight in has a high pucker factor.

But the scenery is spectacular.

As airports go, landing at Big Creek isn’t easy:

As opposed to a big city airport’s vague sense of unease, landing at Big Creek has an acute sense of unease.

But rolling to a stop at the Big Creek Lodge makes everything ok.

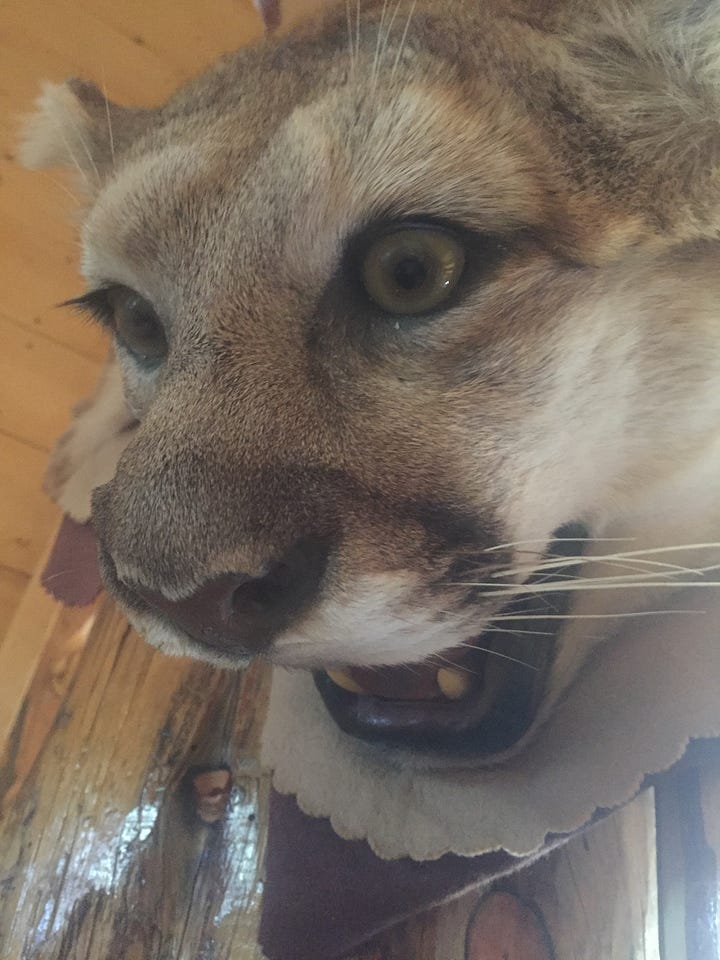

The only unease at Big Creek Airport comes from the taxidermy.

And the food beats any big city airport’s teriyaki chicken and soft pretzels.

And there’s acoustic entertainment.

But cutthroat trout are the real entertainment.

My trips to Big Creek were in a Cessna 182 which, when airborne, seems as sturdy and powerful as a vintage VW Beetle. But when piloted by my friend Galen Hanselman, all panic disappeared.

Flying with Galen would make you feel as if you’re in your mother’s arms (assuming, of course, that your mother has arms).

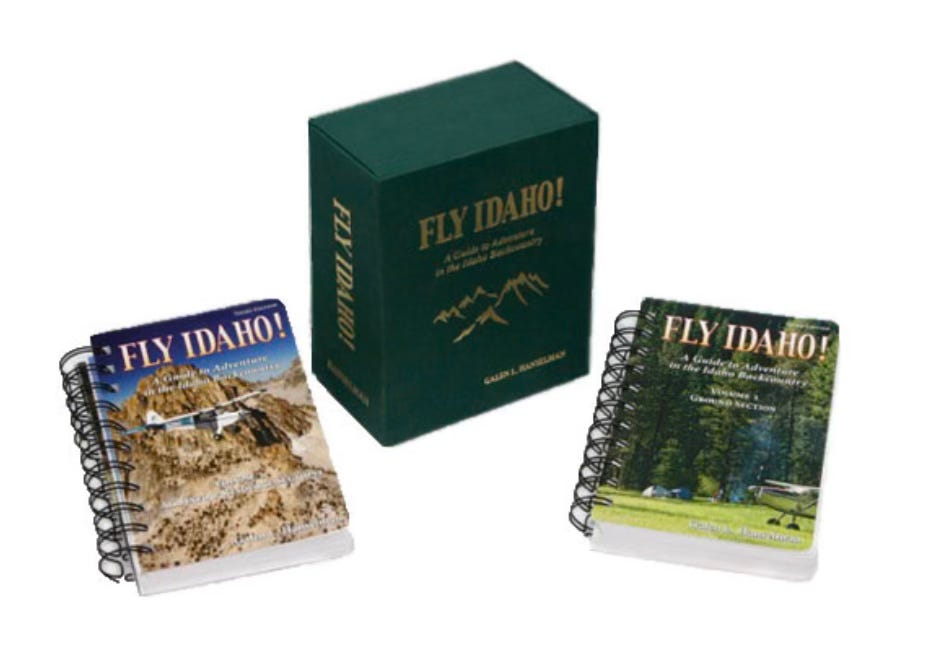

He spent decades in the Idaho backcountry - and the backcountry of Utah, Montana, and Mexico - documenting airstrips. He measured them, inspected them, photographed them, and researched them.

He ended up in many places he wasn’t supposed to be and was detained thirty-seven times by military, police, and federales. But what came from his diligence was a timeless series of books revered by backcountry pilots. He printed them with spiral binding so they could balance on a pilot’s knee for added assurance during an approach.

Galen was a gift to backcountry pilots, but real estateurs can also benefit from his work.

Galen developed a ranking system for each airstrip called the “Relative Hazard Index” which considered runway gradients, runway-elevation profiles, and surrounding terrain elevation models, visibility, and obstacles to rank the difficulty of landing and takeoff as a number between 1 and 50.

Sometimes he added more color than a simple number, like with a place in Utah called Robbers Roost:

“Caution: Isolated, remote, cowboy-outlaw country. Don’t attempt to leave this desert maze by any means other than an airplane.”

Thinking there had to be more nuance than just numbers, I asked Galen how he developed conviction in his rankings.

“There’s a real sense of clarity that comes from piling up an airplane”.

Galen had his share of mishaps, including one that should’ve been deadly with his son in tow. That one bothered him and was the catalyst to get even more serious about his RHI rankings.

Galen did the work so other pilots didn’t have to. In the same way, we real estateurs can avoid a fiery crash by developing our own Relative Hazard Index - and supplementing it with other’s knowledge. Especially the knowledge of experienced old coots.

I make a habit of it - with the right people, knowledge, and food there’s no reason to be depressed at airports (at least some of them).

Galen Hanselman was everything that is good and right with America. He’s not with us anymore and the backcountry isn’t the same without him. Rest easy, my friend.

Eric always look forward to your commentary accompanying your travels.

awesome