The thing that doesn't fit is the thing that's the most interesting: the part that doesn't go according to what you expected.

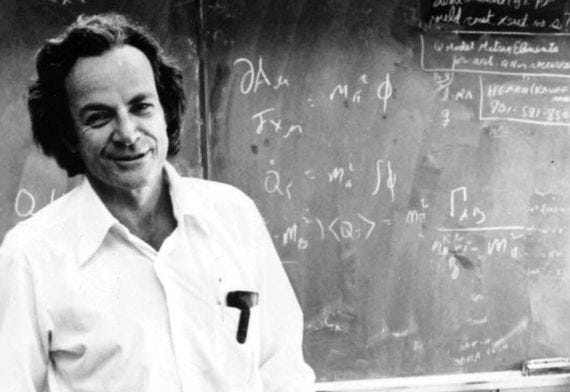

Richard P. Feynman

If he wasn't one of history’s most accomplished theoretical physicists, producing groundbreaking work on quantum electrodynamics - and other impossible to understand topics - Richard Feynman would’ve made a wonderful real estateur. He broke down complex theories to simple line drawings, “Feynman Diagrams” not unlike a site plan one of us knuckle-dragging developers might sketch on the back of a cocktail napkin. But even more useful, Feynman identified the developer’s achilles heel:

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Try as we might to not fool ourselves, sometimes we do. Things don’t always go as planned; in fact, in real estate development, they never do. And that’s where the good stuff is.

One of our earliest projects - that almost didn't happen - was buying this quirky joint:

From the outset it had all the components of a sweet opportunity: a premier corner in a rich Los Angeles suburb, a disinterested owner, and a back door path to buying it. The theater building was owned by a Hollywood icon but controlled by the trust department at a stodgy bank. The building was obsolescent, too small to make any real money as a theater, and with lots of deferred maintenance.

We learned about it from an offhand comment from someone in the real estate department at the theater chain that leased the building: “hey what do you know about LA? We’ve got a lease we need to get out of.”

The bad news was the theater was losing money. The good news, for us, was they had a few decades left on a lease at a laughable lease rate. Because their rent was so low, for so long, the building’s value was impaired.

Another key feature of the lease was it allowed the tenant to assign it with no restrictions. Commercial leases usually require the replacement tenant to have equal or better financial wherewithal than the assigning tenant. In this case, the theater had the right to get out of their obligation by assigning the lease to whoever they wanted, even a couple of chumps like us.

We figured we could get control of the lease then use it as leverage to buy the building at a discount because the only thing worth less than a building with low rent on a long term lease is a building with low rent on a long term lease with tenants that have shaky credit.

But to do any of this we needed money and so we went to see one of the smartest, richest, most experienced real estate operators we knew. He and his partner had done projects like this throughout California for over 50 years.

We met in their nondescript office of metal desks and fluorescent lights and explained our caper. They were generous with their time, and with fevered excitement - even talking over each other at times - explained in grand detail how we were borderline morons.

They listed every possible thing that could go wrong: entitlements, financing markets, latent construction defects, lease-up risk, earthquake issues, and potential environmental clean up.

We sat with our heads hung low, assailed by an endless barrage of gotchas. Needing a laugh, I couldn’t help but ask “so does this mean you’re not interested?” before we headed for the door.

Not to be confused by a bunch of facts, we relented to our deal fever and kept moving.

We took assignment of the lease and, as their new tenant, went to see the stodgy bankers - introducing ourselves with a big smile and questionable financials.

The meeting didn’t go as planned. They agreed to sell the building, just not to us.

Listing the building for sale with a prominent broker was the stodgiest thing they could do, making sure the entire marketplace knew about the opportunity. We found ourselves with a boat anchor of a lease around our necks, and to buy the building we were forced to compete with the biggest sharks in one of the world’s most cutthroat real estate markets.

The marketing period was short, but all the local warlords and some of the big national shops showed up and made a bid. The good news is we won the bid, the bad news was we offered to pay more than anyone else, and pay it on the shortest timeline.

We had good reasons. We had already done most of the due diligence - things like surveys, building condition reports, environmental assessments, and title reports - so we knew what we were getting into as far as the property was concerned. And, we had a wink and a nod from a potential anchor tenant: Tiffany & Co.

Our plan was to chop the existing building into smaller spaces, transforming the lame 80’s art deco facade into a classic rhythm of individual storefronts with a small tower on the corner for the iconic Tiffany Atlas.

We had thirty days to come up with millions of dollars we didn’t have or else lose the $800,000 deposit we’d put up. Nothing creates singular focus than the prospect of losing a lot of hard-earned dough, so we hit the pavement.

A name-brand family office stepped right up and gave us a commitment. There’s nothing like that feeling of relief, having a capable, established group agree to back you and knowing your deposit is safe.

We met the next week on site to firm up details, only to get that sinking feeling that the investor’s representative - the person we’d be dealing with - was a jerk. Such a jerk that we had to break up before the lunch was over.

Our collars got tighter as time wound down. With two weeks left, and after a whirlwind of meetings, a top investment management firm stepped up to back us. In theory.

They had the money, but we had the property. We negotiated for the remaining two weeks, playing it cool, suppressing the terror of losing our deposit. On the final day of our contract we agreed, in theory, to terms.

We would partner on the project, they would provide the millions required to close and the millions more to renovate it. We would lease the building and oversee the design. All we needed was the final partnership document to get signed by 5pm. No big deal.

But it is a big deal when, at 3:00pm, there’s no final document and the investor isn’t answering their phone. A few minutes later they called to discuss some “new thinking” on the deal, a different set of terms, given the risks involved.

There’s a certain feeling every real estateur gets during these 11th hour high-stakes negotiations, and it’s not just watery stools. The trick is having properly evaluated the strength of one’s relative position and having the conviction to stand by it.

Our negotiating standoff remained at 4:59pm but we took a deep breath and resolved to let our deposit go. At 5:00pm a fax (yes, these were the days of fax machines) came through with the partnership agreement’s signed signature page.

We closed on the property thanks to our partner’s money. The redevelopment experienced every single problem identified by the original investor prospect. Every single one. But we sidestepped them for the most part.

We sold the property almost two decades ago. It was a ridiculous financial success, and almost all of the countless risks we took just happened to go our way. I wouldn't do it again, knowing what we now know.

Progress requires inexperience. And sometimes conviction is more valuable than facts. But it’s the unexpected, as Mr. Feynman said, that leads us to what’s most interesting.

Phenomenal.

To the naive go the spoils. 😂